The Return of the White Brother

By Justin McCarthy

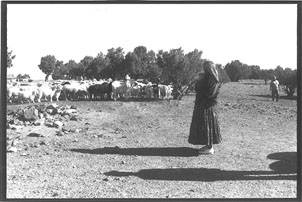

Rena Babbit-Lane, a weaver who lives at Big Mountain, is pictured here with other resisters at Big Mountain, where Native Americans refuse to leave despite pressure from officials who want to mine the land for coal.

When one mentions genocide in America, we often think of the Calvary of the 19th century killing the Indians sleeping in their buffalo-skinned lodges. Sadly enough, genocide continues today, under the guise of official government policy, a policy of using Native American lands for nuclear weapons testing, leasing for uranium and coal mining and the forced removal and relocation of native people.

So that extractive industries such as coal mining could profit from the land, Native people have been forcibly relocated from such places as Big Mountain and Black Mesa in Arizona, to lands in New Mexico that Natives say are poisoned with uranium tailings and nuclear waste. Both the Navajo and Hopi natives experienced great unrest in relocating, as people became ill and died while living on new lands, or were (and still are) subject to great stress if they chose to stay in Arizona.

Twelve thousand Navajos that have given in to forced relocation have met cancer and death in a foreign land. The 400,000 acres of "New Lands" for Navajos bought by the Federal government is on the site of the world's worst radioactive spill ever known. In 1976, there was a partial break in the earthen dam to hold water-laden uranium tailings in Shiprock, N.M. Three years later, the dam broke entirely, releasing 370,000 cubic meters of radioactive water. Surrounding lands are now contaminated and the Rio Puerco River has been affected miles downstream. The land was deemed to exceed 100 times the maximum safe level of radiation.

One-quarter of the first group that moved there in 1980 were dead by 1986. The remaining population suffers from birth defects twice the national average, and their livestock continually die off.

"Traditional" natives have called upon the United Nations to hear their pleas, bringing U.N. condemnation of U.S. policy of Native people at Big Mountain and Black Mesa in the 1980s.

Slowly, the word is getting out as different Natives and activists start working together to achieve common goals of environmental and social justice. As Western Shoshone Spiritual Elder Corbin Harney puts it, "We came out behind the bush." The hurdles of different groups working together to get the information out of the rural Southwest has been difficult, involving big corporations, mining interests, government entities and many politicians, including former presidential hopeful John McCain.

The Hopi and Navajo historic dealings with the United States are not only complex and tragic, but with the help of the government, have created land disputes amongst the Natives.

The Indian Reorganization Act

In 1932, John Collier became the commissioner of the BIA under the Roosevelt Administration. Collier, who thought of himself as a champion of Native people, introduced the 1934 Indian Reorganization Act (IRA). The IRA formed tribal governments that were formally recognized, instead of traditional councils that, with the new system, were discouraged. The new IRA tribal councils were often comprised of Natives who had become Christians or Mormons, were educated in reform boarding schools, were assimilated to white culture, and in some tribes, were mixed-blooded Anglos. Traditionals don't generally recognize these government-mandated tribal councils, even today.The IRA councils were often given tribal government jobs through unfair selection processes. Some proceeded to sign contracts that went against traditional Native beliefs, such as leasing sacred lands. Coupled with this change, the government imposed a blood quantum, which decided who was recognized as a tribal member by the U.S. government, instead of the tribal community itself.

"The Wheeler-Howard Act (IRA), provides only one form of government for the Indian and that is communal or cooperative form of living. John Collier said he was going to give the Indian self government. If he was going to give us self government he would let us set up a form of government we wanted to live under. He would give us the right to continue to live under our old tribal customs if we wanted to."

-Alice Johnson, Seneca activist, 1993

History and information of U.S. government agencies such as the BIA, IRA/BIA tribal governments and mining interests is contradictory. The ancient Hopi lands have steadily been settled by Navajo as their large and growing population moved west. The Navajo Nation's land base was enlarged several times on mostly Hopi land, but also on Southern Ute and San Juan Southern Piautes lands (the San Juan Piautes no longer have a land base, it was all lost to the Navajo Nation).Persistent land disputes

The Hopi's reservation boundaries were placed in the 1880s. The reservation was much smaller than their traditional lands, which were squatted on by Navajos. Official land disputes have ensued ever since between the tribes.The BIA-recognized Hopi tribal council has tried to battle the Navajo Nation in the courts, only to lose more land to the Navajos. Mining interests - especially the coal industry - have exploited tribal councils in a manner that, in the end, benefits only the industry.

One of the most important cases that paved the way for coal mining on Hopi and Navajo lands was Healing vs. Jones, wherein in 1958, a special act of Congress allowed the two tribes to sue each other. In the decision, the Hopi tribal council lost nearly 50 percent of its reservation. The remaining lands had been designated "joint use areas" for both tribes, and were managed by the BIA with heavy grazing activity. It was noted by observers at the time that the BIA Navajo council would have been more friendly to coal mining interests, but the majority of the BIA Hopi council objected to leasing their lands for that purpose. Unfortunately, the BIA Navajo council had already signed mining leases with a large coal mining company, Peabody Coal, so the Hopi's only choice was to either receive or not receive mining royalties on mandated leases. They gave in, in 1966.

Peabody Coal Company is a multi-national corporation that announced its intentions to mine the area, which encompasses 100 square miles, in 1980. According to the U.S. Geological Survey, about 8 billion tons of coal lie under Black Mesa. Like similar corporations, the company has gone through many owners and changes of name. It is currently British owned, and is the world's largest privately held coal company.

From 1972-74, Hopi lands were further partitioned with about half of the lands going to the direct control of the Navajo Nation under the Partitioning Act, which was supported by Arizona Senator John McCain.

In the deal, a small number of Hopi families were moved off of Navajo lands onto a Hopi reservation, but the Navajo resisters - those people who refuse to be relocated - at Big Mountain still live on Hopi-controlled lands. Because this land has been sought-after by Peabody, the resisters have to contend with both an unfriendly BIA Hopi Council and a mix of harassing Federal agents. The Navajo Nation has not given up fighting for control of the lands, for royalties and especially because relocation onto "New Lands" means living on some of the most poisoned soil in the country.

McCain, the so-called reformer and "champion of integrity" authorized this genocidal bill. Afterwards, it was signed by President Ford into law. This past summer, McCain was reminded of his "helpful hand" in genocide at the Shadow Convention, which occurred during the same time as the Republican Convention, but was attended mostly by left-wing activists not interested in the major-party gathering. McCain was invited to speak on campaign finance reform, but was shouted off the podium by chants of "Black Mesa!" Peace activists do not forget.

Living in a wasteland

Those several hundred Navajo families that have resisted relocation at Black Mesa-Big Mountain are mostly comprised of elders who face many challenges. The 1974 Relocation Act, which was supposed to preserve Hopi lands from Navajo squatters, was really an attempt by mining interests to take more land.The law is more commonly known as the "Bennet Freeze" (named after the Secretary of the Interior). It does not allow resisters to repair, complete or add infrastructure (including repair of a broken window or a leak in a roof), build new homes, wells or businesses, or maintain dirt roads. Federal agents, including the BIA and Hopi Tribal Police, continue to harass resisters (there are allegations of direct physical beating) and impound livestock over unjust and complicated grazing permits. The Hopi Tribal Council is currently suing the BIA over the ability to issue gazing permits on "joint use authority" lands. The confiscated livestock is usually resold by the BIA for profit.

The traditionals of both tribes seem to work together, but the tribal councils do not get along - a point the BIA has exploited. These unresolved issues of contention result in more mining by extractive industries.

"The general perspective of most Indian press coverage has been that this is not 'Indian vs. Indian,' but white financial interests (and politicians that service them) playing off Indians against each other to gain financial and other advantages for themselves," said Paula Giese, a historian.

Navajo resister Rena Babbit-Lane, a weaver who lives at Big Mountain, expressed her people's struggle: "There's a lot of pollution from Peabody Coal Mine and a lot of the people are sick from it. It's our land on this Mesa - they don't need to bother us. They cannot impound anymore. What they are doing to us is making us sick. There has been destruction of grave sites. They're crushing cement foundations of people's homes that have been abandoned because of relocation. They are taking. It shows you how they are greedy. They're erasing all the evidence of genocide. Two burials of our family were destroyed. They were torn down and taken somewhere."

BIA Reform?

In September 2000, the BIA celebrated its 175-year anniversary. Kevin Gover, Pawnee and head of the agency, apologized for the BIA's "legacy of racism and inhumanity." Gover is the highest U.S. ranking official to ever make such a statement. Still, the resisters wait for any change in BIA official policy. What is truly sad is the fact that genocide lives well in America as we start the 21st century. The price of human lives has been paid for coal and obedient puppet governments. The civil liberties that so many of us take for granted do not exist for the resisters. In our American dream, too many have been left behind. They cry silent to a corporate media. If America does not come to terms with its past, how will we avoid repeating these crimes in this new millennium? If we continue energy and environmental policies of the past century, how will we survive?Hopi Elder Thomas Banyacya made this statement about the Hopi/Navajo situation in a 1971 letter addressed to President Nixon, signed by other traditional village elders:

"The white man, through his insensitivity to the way of Nature, has desecrated the face of Mother Earth. The white man's advanced technological capacity has occurred as a result of his lack of regard for the spiritual path and for the way of all living things. The white man's desire for material possessions and power has blinded him to the pain he has caused the Mother Earth by his quest for what he calls natural resources. And the path of the Great Spirit has become difficult to see by almost all men, even by many Indians who have chosen instead to follow the path of the white man ..."